By David Allan, President, Virtuix Inc.

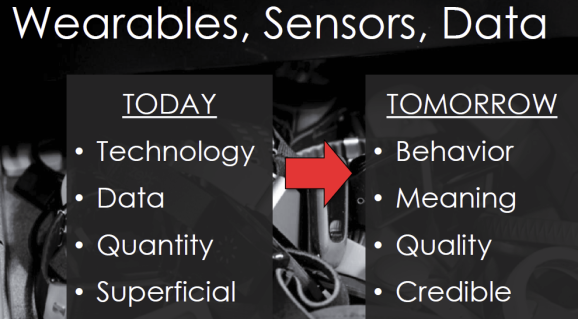

Walking the aisles at CES, you are hard-pressed to find a single product that doesn’t contain at least one sensor. The latest iPhones add a barometric sensor to at least a dozen others. By some predictions, a trillion-sensor world is not far off. Yet what benefits, really, will this ubiquity of sensors deliver? We put this question, and others, to the speakers at the Sensors and MEMS Technology conference.

To Karen Lightman, Executive Director of the MEMS Industry Group, the answer lies in pairing sensors with data analytics. She notes that “MEMS and sensors are already fulfilling the promise to make the world a better place, from airbags and active rollover protection in our cars to the smart toaster that ensures my daughter’s morning bagel won’t be burnt. By combining sensors with data analytics, we can increase that intelligence exponentially.”

An example is biometric measurements, which traditionally suffer from undersampling. Your doctor checks your pulse or blood pressure just once in a while, whereas a typical day may see wild fluctuations. David He, Chief Scientist at Quanttus Inc., predicts a convergence between consumer and clinical use of wearable sensors. Noting that cardiovascular disease and other chronic conditions often go undiagnosed, he foresees ICU-quality wearable sensors that measure your vital signs as you undergo daily activities, relying on enormous datasets to detect problematic patterns. “While everyone is looking for the killer app in wearables,” he urges, “we should be looking for the un-killer app.”

Date analytics paired with ubiquitous sensors promise to improve and even save lives (Image courtesy of Quanttus Inc.)

Ben Waber, CEO of Sociometric Solutions, puts sensor data to a radically different use. His firm outfits employees of large companies with sensor-equipped badges that track their interactions. “In any industry the interaction between employees is the most important thing that happens at work,” he told CNN. His badges use motion sensors to follow users as they mix with others in the office and to monitor their posture while seated (slouching suggests low energy). A microphone measures tone of voice, rapidity of speech, and whether a person dominates meetings or allows others to speak in turn.

Waber claims employees can use the results to improve performance and job satisfaction. “You can see the top performers and change your behavior accordingly, to be happier and more productive. In a retail store, you might see that you spend 20% of your time talking to customers, but the guy who makes the most commission spends 30%.” He adds, “I can point to thousands of people who say they like their jobs better.”

Steven LeBoeuf, president of Valencell, points to a problem he calls “death by discharge,” meaning the tendency of novel wearables to “land in the sock drawer before insights can be made” because users tire of keeping them charged. His firm promotes a category he calls “hearables”: sensors added to earphones—powered from a standard jack—that measure pulse, breathing, blood pressure, and even blood-oxygen saturation, all from gossamer-thin vessels on the ear called “arterioles.” Yet measurements alone, he cautions, fall short without comparative analytics. “Human subject testing is a different animal altogether…extensive human subject validation is required for accurate biometric sensing.”

Data is moving from physical to mental. Rana el Kaliouby’s company, Affectiva, combines sensor data with analytics to monitor emotional states, detecting stress, loneliness, depression, and productivity. She foresees a sensor-driven “emotion economy” where devices act on our feelings. She told The New Yorker, “We put together a patent application for a system that could dynamically price advertising depending on how people responded to it.”

Indeed, patent filings abound for mood-sensing devices. Anheuser-Busch’s application for an “intelligent beverage container,” notes that without it, sports fans at games “wishing to use their beverage containers to express emotion are limited to, for example, raising a bottle to express solidarity with a team.”

Now stonily indifferent to our feelings, our devices may acquire an almost-human sympathy. “I think that, ten years down the line,” predicts Affectiva’s Kaliouby, “we won’t remember what it was like when we couldn’t just frown at our device, and our device would say, ‘Oh, you didn’t like that, did you?’”